Latest Meditative Story

Move forward without moving on

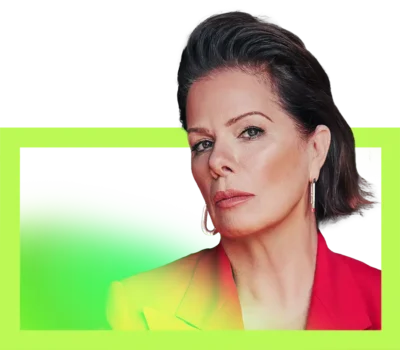

Kelly Rizzo

Host

Kelly Rizzo, Host

When her husband Bob Saget passes away without warning, Kelly Rizzo must find a way to honor her memories even as her life moves forward.

When her husband Bob Saget passes away without warning, Kelly Rizzo must find a way to honor her memories even as her life moves forward.

Mindfulness, delivered

Your weekly reminder to take time to calm, center and recharge.

Meditative Story combines stories with meditation prompts — all surrounded by cinematic music.

Trending Stories

Every episode is centered around a wellness topic for listeners to take into their daily lives.

Meet Your Meditative Story Host

Rohan Gunatillake is the host of Meditative Story. By artfully crafting meditations to compliment each guest’s story, Rohan blends mindfulness with narrative to create a unique listening experience.

Trending Rohan Meditations

Meditative Story Presents...

Sleep Song

A companion to our stories

Created by our in-house composers, Sleep Song is designed to help you enter a relaxed state, conducive to a good night’s rest.

Our notable storytellers share their experiences as an alternative way into a mindfulness practice.

Trending Storytellers

Follow Meditative Story